11. Stabiae, Varano (?). Villa

urbana scavata all'inizio del 1782.

Stabiae, Varano (?). Urban villa excavated in early 1782.

Bibliography

Kockel V., 1985. Funde und Forschungen in den Vesuvstadten 1: Archäologischer Anzeiger, Heft 3. 1985, n. 11, p. 534.

Moorman E. in Dobbins, J. J. and Foss, P. W., 2007. The World of Pompeii. Oxford: Routledge, p. 436-7, fig. 28,1.

Ruggiero M.,

1881. Degli scavi di Stabia dal 1749 al

1782, Naples, p. 355-6, Tav. 18.

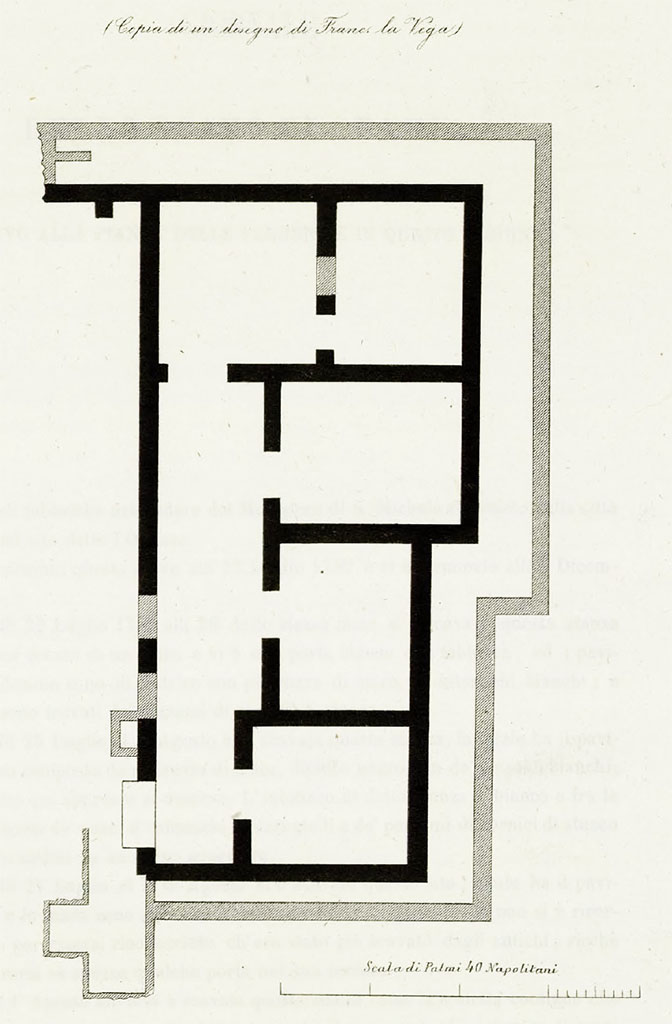

Villa at Stabiae Varano. Plan copied from a drawing by Francesco La Vega.

See Ruggiero M., 1881. Degli scavi di Stabia dal 1749 al 1782, Naples. Tav. 18.

Ruggiero 1881

Excavation report

All that remains of this building is a copy of the plan (without the numbers from the lost Journal) and the mosaics of the floors of four rooms drawn by La Vega; two of these are published with the said plan in Table XVIII and two others have been left out, but can be seen in the National Museum, one in the middle of the first room of the vases and the other in the middle of the second room of the Santangelo collection.

Of

all the buildings discovered at Stabia, I consider only one to be an urban

villa, that which was excavated in the early months of 1782. It was on one

level and had no atrium, its place taken by an entrance hallway, iter, which gave access to the cubicula, providing

communication between them; which completely covered by the roof, would have

been left without light, without two large windows a short height from the

ground, from which the beautiful view of Vesuvius, Sarno, Pompeii, Oplontis, Herculaneum,

and Naples could be enjoyed and of many other houses and gardens on the shore

of the placid and voluptuous Tyrrhenian sea. These

large windows, from which one could see externally, were called valvatae (VITRUV, VI, chapter

3, PLIN, Epistles, II, chapter 17, 5, Iib, V, chapter

6, 19) ; but the bifores valvae

(Ovid, Metam, lib II, v. 4) not only noticed the shutters,

as in that place of Petronius, videbamus

omnia for foramen valvae (Satyr., chapter 96), but sometimes also

the double wooden frame equipped with glass or thin crusts of stone similar to

talcum that the ancients called lapis

specularis; and this is confirmed by the knowledge that windows were

commonly made without shutters, as is the case of the Pompeian houses and

various classical places, as among others by the following from Ovid; reseratis aurea · valvis Atria tota patent

(Metam, IV, v. 761), which cannot be understood

without supposing the movable and transparent valvae on their hinges. See also what

Becker said bout the windows in Gallus

(tom I, page 99), and the place in the Anthologia quoted by Avellino in his

description of the fourth Pompeian house (page 13, note 1)

The lack of the atrium and of any other open courtyard, (Gr…), led me to believe at first that this villa was built according to the custom of the Greeks, which according to Vitruvius atriis ... non utuntur, neque ea aedificant; sed ab janua introeuntibus itinera fa ciunt latitudinibus non spatiosis (lib. VI, chap. 7), so much so that in many monuments of Stabiae one can see a great imitation of Greek art and little sympathy with Roman customs; but two important observations exclude this easy conjecture and otherwise explain the lack of the atrium in a Roman house. The first arises from a passage from the same Vitruvius; qui communi sunt fortuna, non necessaria magnifica vestibula, nec tablina, neque atria (lib. VI, chap. 5); since such members destined to the reception of the people who went to officiate the master of the house, they were not necessary in the houses of those, quod ... . aliis officia praestant ambiendo, quae ab aliis ambiuntur (Vitruv., I. c., and there the note by Marini, tom. II, page 29). The second is that in many Pompeian, Stabian and Herculaneum paintings, portraying landscapes and views, topiary work (PLIN., Hist., Lib. XXXV, chap. 37), we see one and two-storey buildings with large windows, covered entirely by the pectinatum roof, without any opening for the compluvium, which is a sure indication of the absolute absence of the atrium. It must therefore be believed that small houses without atriums were frequent in the countryside, both because they generally belonged to people of mediocre fortune; or because they were exposed to the rigors of the seasons, it was useful to preserve them from the cold by closing the roof above, or to temper the heat of the same by means of spacious windows.

To the right of the hall there were three rooms, with elegant paintings and beautiful mosaic floors, of which the first two can be called cubicula or dormitoria, the third a triclinium, with its larger proportions. Another room was at the end of the entrance hallway, and had a wide door without shutters like the tablinum, which it seems to replace; lastly an oecus quadratus followed, in the most hidden and secluded part of the house.

It should be noted that the kitchen with its appliances was

outside the built-up area, in an enclosure near the entrance door of the villa,

which on the other side had a well or cistern adjoining the front of the

building. Furthermore, that being this villa built on other remains buried by

the eruption of the year 79 e v., and in a plane somewhat lower than that of

the neighbouring fields, to protect it from the damp they had surrounded it

with a ditch, 2 palms wide on the left, 5 palms to right and behind and 4 palms

deep; which, because it was not filled with earth, had the embankment of a wall

parallel to the external faces of the building, and which were covered with

white plaster, like the visible walls of the wall itself. Fiorelli (Op. Cit., Tom. II, pages 423-24).

See Ruggiero M., 1881. Degli scavi

di Stabia dal 1749 al 1782, Naples. p. 355-6.

Relazione di scavo

Di questo

edifizio avanza solamente una copia della pianta (senza il riscontro dei numeri

relativi al Giornale perduto) e i musaici dei pavimenti di quattro stanze

disegnati dal la Vega; due dei quali si pubblicano con la detta pianta nella

Tav. XVIII e due altri si tralasciano, potendosi vederli nel Museo nazionale,

l'uno nel mezzo della prima sala dei vasi e l'altro parimente nel mezzo della

seconda sala della collezione Santangelo.

Di tutti gli

edifizi scoperti a Stabia reputo villa urbana quella solamente che fu scavata

nei primi mesi del 1782. Essa era ad un sol piano e non aveva atrio, facendone

le veci un androne, iter, che dava adito ai cubicoli, e li metteva in

comunicazione tra loro; il quale coperto interamente dal tetto, sarebbe rimasto

privo di luce, senza due grandi finestre a poca altezza dal suolo, da cui si

godeva la bellissima vista del Vesuvio, del Sarno, di Pompei, di Oplonti,

d'Ercolano, di Napoli e di tante altre case e giardini in riva al placido e

voluttuoso Tirreno. Queste grandi finestre, dalle quali si vedeva esternamente,

furono dette valvatae (VITRUV., lib.

VI, cap. 3; PLIN., Epist. lib.

II, cap. 17, 5; Iib. V, cap. 6, 19); ma le bifores valvae (Ovid., Metam . lib. II, v. 4) non di notarono solamente le imposte, come

in quel luogo di Petronio, videbamus omnia per foramen valvae (Satyr., cap. 96), ma

talvolta anche il duplice telaio di legno fornito di vetri o di sottili cruste di pietra simile al talco che gli antichi

appellarono lapis

specularis; e ciò si

conferma dal sapere che le finestre si facevano comunemente prive d' imposte,

come s'ha dalle case pompeiane e da varii luoghi de'

classici, come tra gli altri dal seguente di Ovidio; reseratis aurea ·valvis Atria tota patent ( Metam. , lib. IV, v. 761), che non può intendersi senza supporre le valvae mobili su i loro

cardini, e trasparenti. Si vegga inoltre ciò che

delle finestre ha detto il Becker nel Gallus (tom. I, pag. 99), ed il luogo dell'Anthologia richiamato dall'Avellino nella descrizione della

quarta casa pompeiana (pag. 13, nota 1)

La mancanza

dell'atrio e di qualsivoglia altra corte scoperta, (Gr…), m' indusse a creder sulle prime fabbricala

questa villa secondo il costume dei Greci, che al dir di Vitruvio atriis ... non utuntur, neque ea

aedificant; sed ab janua introeuntibus itinera fa ciunt latitudinibus non

spatiosis (lib. VI, cap. 7), tanto pili che in molti monumenti di

Stabia scorgesi una grande imitazione dell'arte greca

e poca simpatia con le costumanze romane; ma due importanti osservazioni

escludono questa facile conghiettura e spiegano

altrimenti la mancanza dell'atrio in una casa romana. La prima sorge da un

luogo stesso di Vitruvio; qui communi sunt fortuna, non necessaria magnifica

vestibula, nec tablina, neque atria (lib. VI, cap.

5); poichè tali membri destinati al ricevimento delle

persone che si recavano ad officiare il padrone della casa ,

non erano necessarii nelle abitazioni di coloro, quod .. . . aliis officia praestant

ambiendo, quae ab aliis ambiuntur (Vitruv., I. c., ed ivi la nota del Marini, tom.

II, pag. 29). La seconda è che in molte pitture pompeiane, stabiane ed

ercolanesi, ritraenti paesaggi e vedute, topiaria opera (PLIN., Hist., lib. XXXV, cap. 37), si veggono edifizi i ad uno e due piani

con larghe finestre, coperti interamente dal tetto pectinatum, senza niuna apertura pel compluvium, lo che è indizio sicuro dell'assoluta mancanza dell'atrium.

Dee dunque credersi ch'erano frequenti nelle campagne le piccole case

senz'atrio, sia perchè generalmente appartennero a

persone di mediocre fortuna ; sia perchè

esposte al rigor delle stagioni, giovava preservarle dal freddo , chiudendo il

tetto nel disopra, o temperarne gli ardori della state mercè spaziose finestre.

A dritta

dell'androne stavano tre stanze, con eleganti pitture e bellissimi pavimenti a musaico,

di cui le due prime si possono dire cubicula o dormitoria, la terza un triclinium, dalle sue maggiori

proporzioni. Una altra stanza era in fondo dell'androne, ed aveva la porta

larga e senza imposte a simiglianza de' tablini, di

cui sembra facesse le veci; seguiva da ultimo un oecus quadratus,

nel sito più recondito ed appartato della casa.

È da notare

che la cucina con le sue pertinenze stava fuori dell' abitato,

in un recinto presso la porta d'ingresso della villa, che aveva dall'altro lato

un pozzo o cisterna addossata alla fronte dell'edifizio. Inoltre, che

trovandosi questa villa costruita su di altre fabbriche sepolte dalla eruzione

dell'anno 79 e. v., ed in un piano alquanto più basso di quello dei campi

vicini, a garentirla dall' umido l'avevano cinta di

un fosso, largo a sinistra palmi 2, a dritta ed alle spalle palmi 5 e profondo

palmi 4; il quale perchè non fosse colmato di terra,

ebbe l'argine di un muro parallelo alle facce esterne dell'edifizio, eh' erano

ricoperte d'intonaco bianco, come le pareti visibili del muro medesimo.

Fiorelli (Op. cit., tom. II, pag. 423-24).

Vedi Ruggiero M., 1881. Degli scavi

di Stabia dal 1749 al 1782, Naples. p. 355-6.

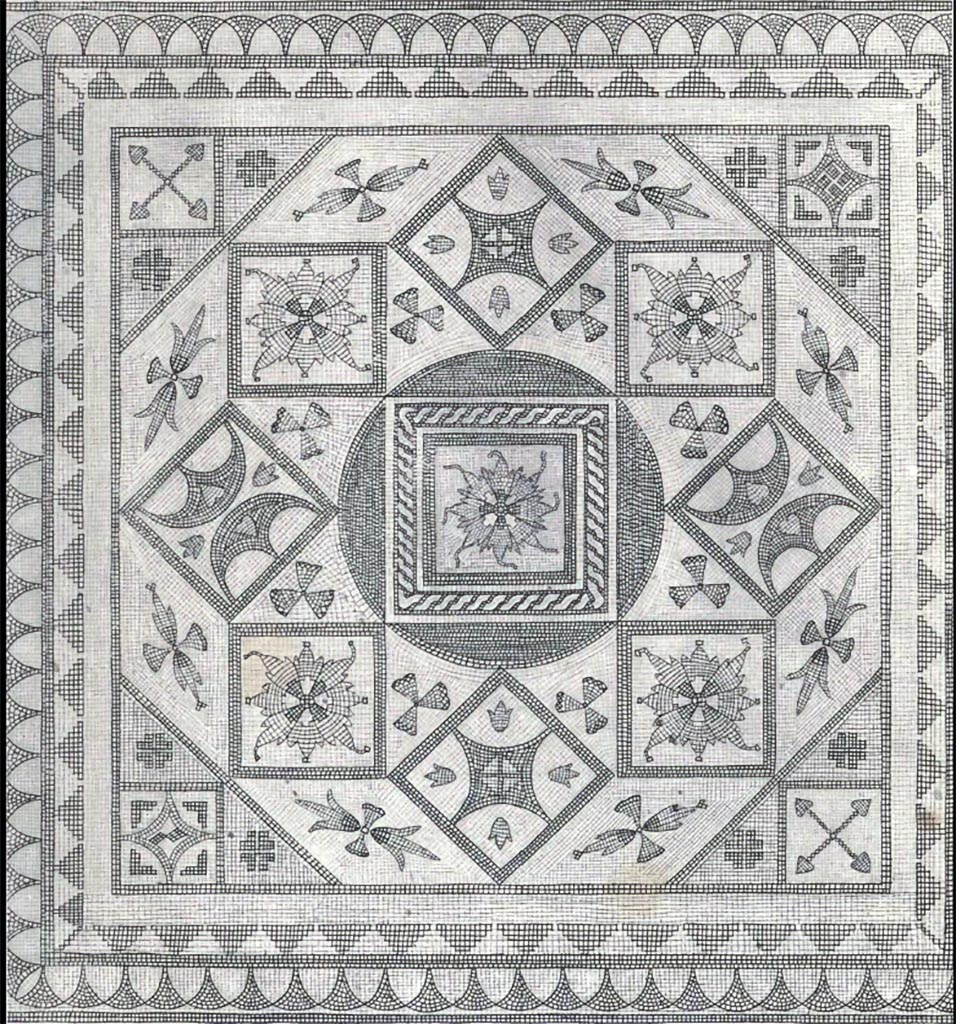

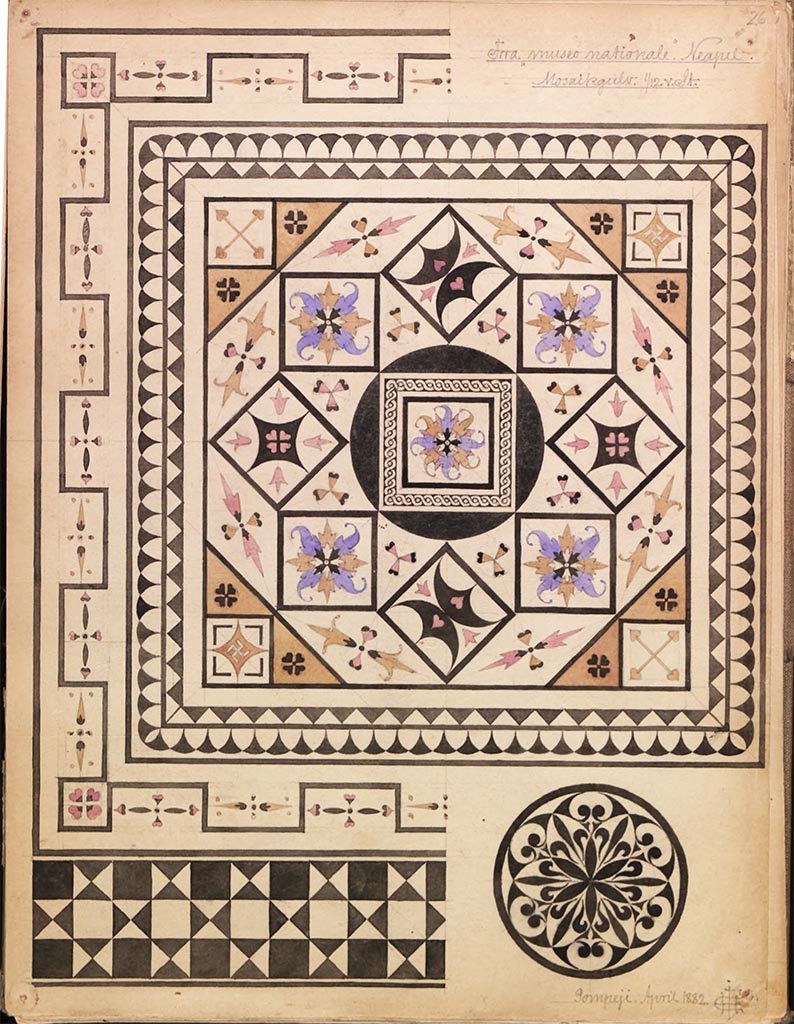

Villa Urbana, Varano,

Stabiae. One of four mosaics,

drawn by Francesco La Vega.

See Ruggiero M., 1881. Degli scavi di Stabia dal 1749 al 1782, Naples. Tav. XVIII.

According to Pisapia, this mosaic as drawn by Ruggiero has since been lost.

See Pisapia, M.

S. 1989, in Mosaici antichi in Italia, Regione prima. Stabia, Roma,

(p.67-70, no. 122, fig.21).

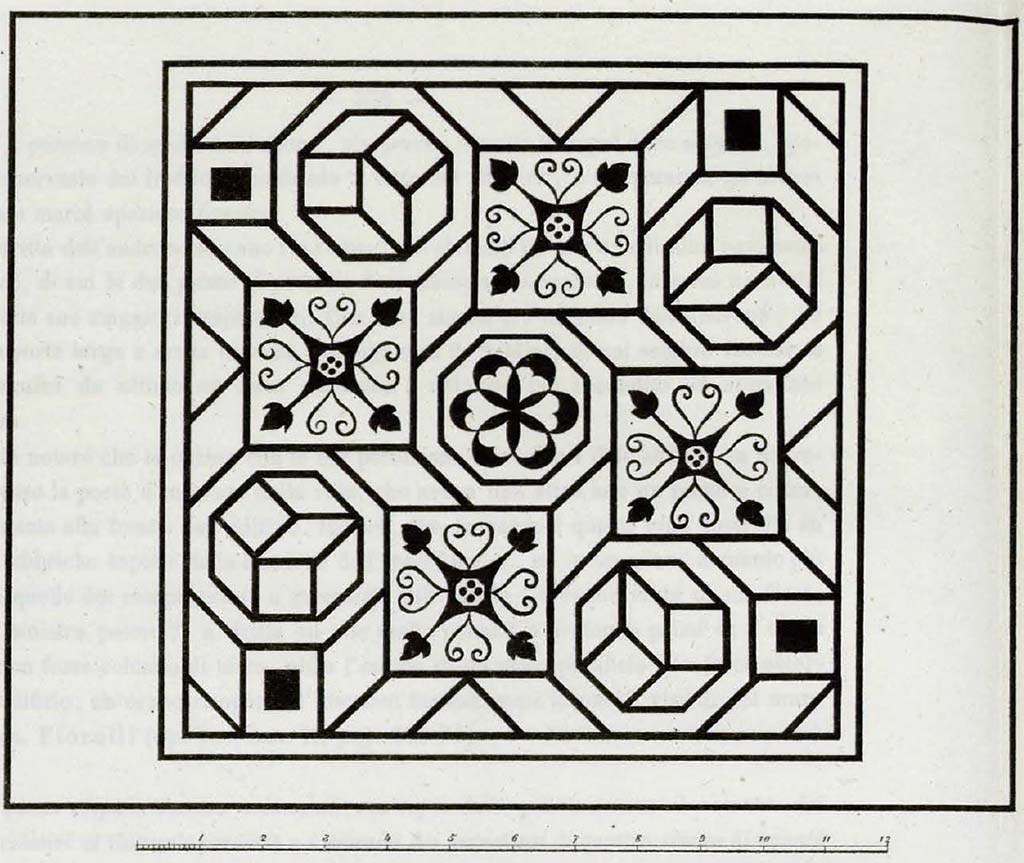

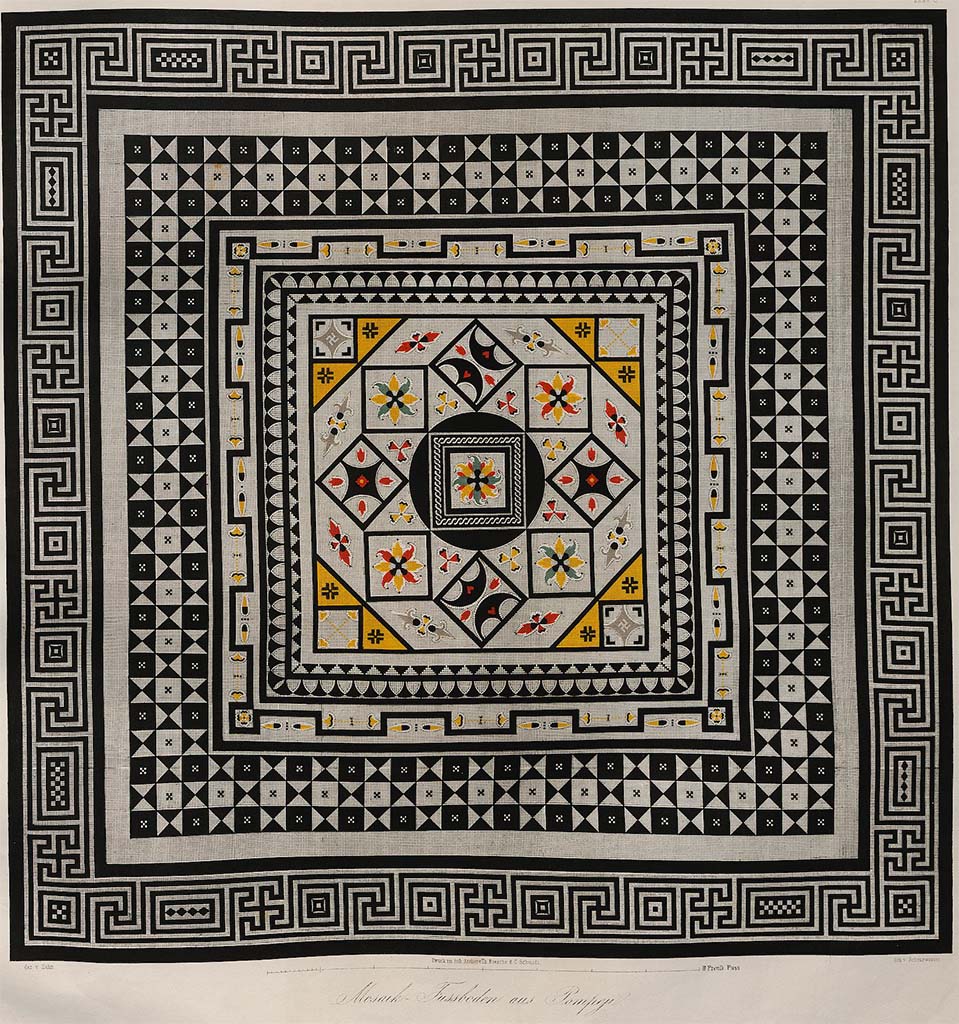

Villa Urbana,

Varano, Stabiae. Second mosaic, drawn

by Francesco La Vega.

See Ruggiero M., 1881. Degli scavi di Stabia dal 1749 al 1782, Naples. Tav. XVIII.

According to Pisapia, this mosaic as drawn by Ruggiero has since been lost.

See Pisapia, M.

S. 1989, in Mosaici antichi in Italia, Regione prima. Stabia, Roma,

(p.67-70, (no. 123, fig.21).

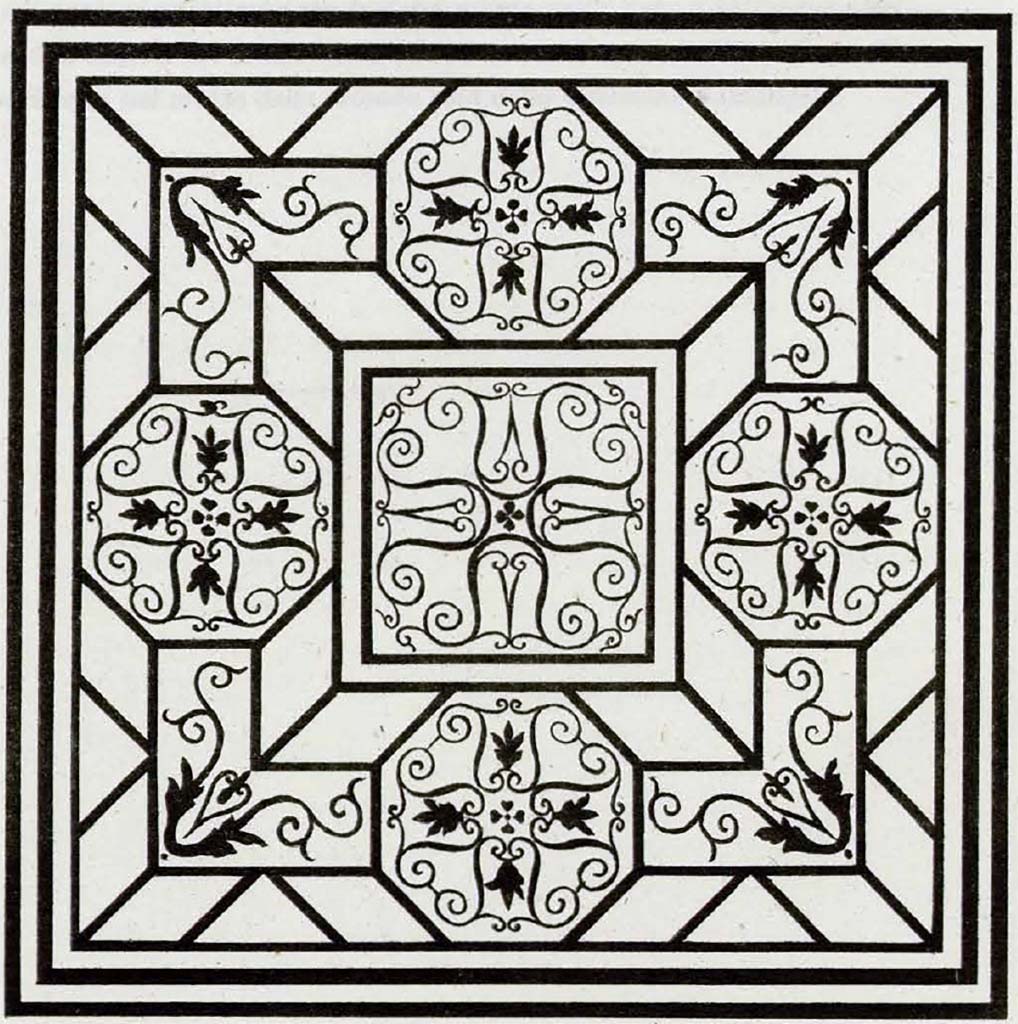

Villa Urbana, Varano, Stabiae. July 2019.

Mosaic floor as seen in room on First Floor in Naples Museum.

Photo courtesy of Giuseppe Ciaramella.

According to Pisapia –

“Of the four rooms that were paved with mosaic floors, the designs that La Vega made of two of these, lost, nos, 122 and 123, are shown in fig.19, while Ruggiero states that the other two are in Real Museo Borbonico and pave the first and second rooms of the Santangelo Collection.

Of this information, however, only part is correct, since, in the first room of the aforementioned Collection, it has been recognised that there is a mosaic from Lucera, while in the second room it is the floor that we indicate as no.124.”

(Dei quattro

ambienti che erano pavimenti a mosaico si riporta alla fig.19 i disegni che il

Vega fece di due di essi n.122 e 123 perduti, mentre il Ruggiero afferma che

gli altri due sono al Real Museo Borbonico e pavimentano la I e la II sala

della Collezione Santangelo.

Di questa

notizia, però, soltanto parte era esatta, poiché, nella I sala della Collezione

citata e stato riconosciuto esservi un mosaico da Lucera, mentre nella II sala

e il pavimento che indichiamo con il no.124).

See Pisapia, M.

S. 1989, in Mosaici antichi in Italia, Regione prima. Stabia, Roma,

(p.67-70, no.124).

According to

Ruggiero –

“Di questo

edificio Avanza solamente una copia della pianta (senza il riscontro dei numeri

relativi al Giornale perduto) e i musaici dei pavimenti di quattro stanze

disegnati dal la Vega; due dei quali si pubblicano con la detta pianta nella

Tav. XVIII e due altri si tralasciano, potendosi vederli nel Museo nazionale,

l’uno nel mezzo della prima sala dei vasi e l’altro parimente nel mezzo della

seconda sala della collezione Santangelo.”

(Of this building remains only a copy of the plan

(without the confirmation of the numbers relating to the lost Giornale) and the

mosaics from the floors of four rooms drawn by La Vega; two of which are

published with the said plan in Tav. XVIII and two others have been left out,

as they can be seen in the National Museum, one in the middle of the first room

of vases and the other equally in the middle of the second room of the

Santangelo collection.)

See Ruggiero, M. (1881). Degli scavi di Stabia dagli 1749 al 1782. (p.356).

Villa Urbana, Varano, Stabiae. July 2019.

Detail of central emblema. Photo courtesy of

Giuseppe Ciaramella.

Villa Urbana, Varano, Stabiae or VIII.2.1 Pompeii. July 2019.

Beautiful central emblema of coloured mosaic set into floor in Naples Archaeological Museum, “Magna Grecia” collection.

Photo courtesy of

Giuseppe Ciaramella.

It is thought this central emblema may be from one

of these two houses, now seen re-set into another mosaic floor.

Many artists in the 19th century have seen and

drawn this mosaic in Naples Museum.

According to Abbate, this mosaic was from either Stabia or Pompeii.

According

to Zanella –

This

mosaic, shown on page 107, fig.49, a drawing by L. Destouches, 1816-1817;

(collection Pierre Pinon); is described as being from Casa di Championnet,

VIII.2.1 in Pompeii.

See Zanella S., 2019. La caccia fu buona: Pour une histoire des

fouilles à Pompéi de Titus à l’Europe. Naples : Centre Jean Bérard, (P.107).

According to Real Museo Borbonico, vol.15, Tav 24 (XXIV), this mosaic is from the Villa of Tiberius on Capri.

According to Pisapia, this mosaic is from Stabia, Villa Urbana.

See Pisapia, M.

S. 1989, in Mosaici antichi in Italia, Regione prima. Stabia, Roma,

(p.67-70, no.124).

Villa Urbana, Varano, Stabiae or VIII.2.1 Pompeii. April

1882.

Painting by Hector Estrup of mosaics in Naples

Museum.

See Skitsebog Hector Estrup (1854-1904) Italiensrejse 1882, pl. 26.

© Danmarks Kunstbibliotek, inventory number 52694.

Villa Urbana, Varano,

Stabiae or VIII.2.1 Pompeii. Pre-1852.

Drawing by Zahn of Pompeii mosaic in

original colours, from Naples Museum.

Zahn describes this as a mosaic from

Pompeii in the colours of the original, currently in the Royal Museum in

Naples.

This paving consists of small pieces of

coloured marble (not glass paste) which are very exactly indicated here, so

that according to this model the execution on a large scale would be very easy.

See Zahn, W.,

1852-59. Die schönsten Ornamente und merkwürdigsten Gemälde aus Pompeji,

Herkulanum und Stabiae: III. Berlin: Reimer, Taf. 6.

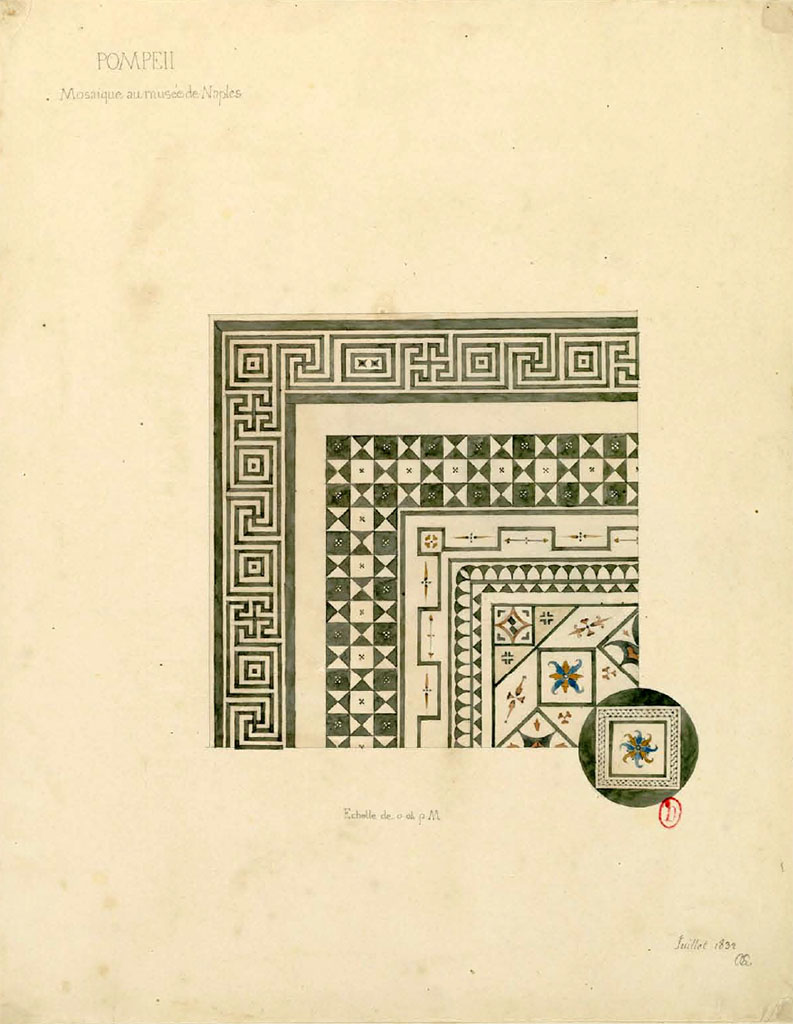

Villa Urbana, Varano, Stabiae or VIII.2.1 Pompeii.

See Raccolta de più belli ed interessanti Dipinti,

Musaici ed altri monumenti rinvenuti negli Scavi di Ercolano, di Pompei, e di

Stabia. 1871. Napoli, pl. 49 and index.

Villa Urbana, Varano,

Stabiae or VIII.2.1 Pompeii. July

1832. Part of floor mosaic drawn by Questel in Naples Museum.

See

Charles-Auguste Questel (1807-1888) Voyage en Italie et Sicile. Août 1831 -

novembre 1832, pl. 36.

INHA identifiant numérique : NUM MS 512. Document placé sous « Licence Ouverte / Open Licence » Etalab

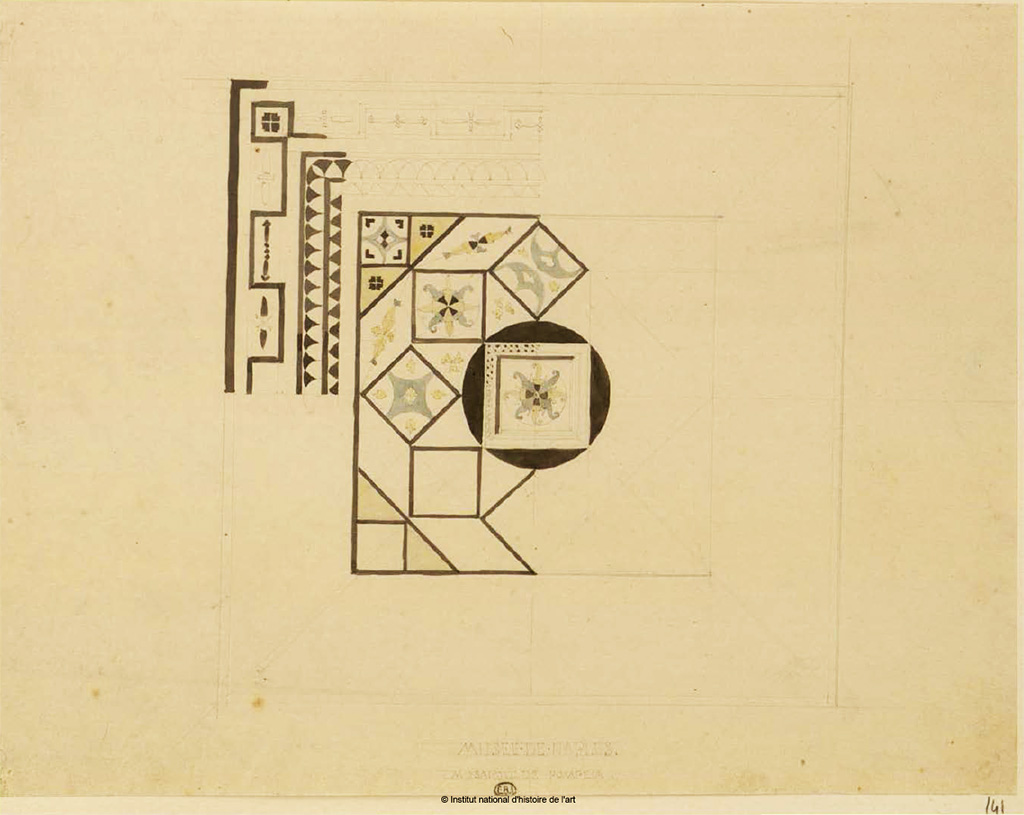

Villa Urbana, Varano, Stabiae or VIII.2.1 Pompeii. Mosaic in

Naples Museum.

See Duban F. Album de dessins d'architecture effectués

par Félix Duban pendant son pensionnat à la Villa Medicis, entre 1823 et 1828: Tome 2,

Pompéi, pl. 141.

INHA Identifiant numérique NUM PC 40425 (2)

https://bibliotheque-numerique.inha.fr/idurl/1/7157 « Licence Ouverte

/ Open Licence »

Etalab